- Home

- Leo Nation

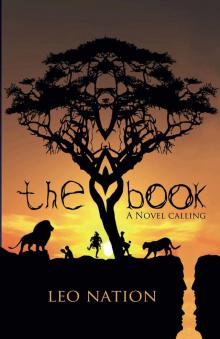

The Book: A Novel Calling

The Book: A Novel Calling Read online

The Book

A Novel Calling

Leo Nation

Cover designed by Phoebe Landrum

If we are to see

The vectored light

Every minute counts

For the Family

Stay holden

And beholden

In Ausperity and High Elationship

The Book

A Novel Calling

Copyright © 2014

All rights reserved

Once upon a time in St. Louis I awoke wanting an express.

“Monsieur, un express s’il vous plaît!”

That was in my mind as I woke up, an inexplicable desire for the kind of coffee I drank in Paris a long time ago. I didn’t drink it anymore and hadn’t for years, but I knew before I got out of bed that morning I would have that express at a coffee shop on Euclid owned by Left Bank Books in the West End. I hadn’t visited that neighborhood in years, and yet, I felt like I had to have that cup of express that day in that location. So I called my office, where I was an employee, and I said, “I feel too good to come in today.” That was the only day I did that. Not before and never since.

I felt sunny, like the rusty colors floating down that crisp October morning; ready to enjoy some time off for good behavior, I drove to the West End to satisfy a sudden longing I could not have explained.

Have you ever had a connection with somebody that makes you feel strange, because it feels kind of cosmic? When I got to the coffee shop I recognized a man like that sitting at a small table in a shaft of morning sunlight squeezing through the other side of the street. As he looked up at a pristine sky, I thought: It seems like this guy’s been waiting here for me.

Every time I ran into Jack, every six months or so, I had a strange but familiar feeling that we had known each other for a long time, despite the fact that we had been introduced only recently as activists on the dioxin problem of Times Beach. Every encounter with this guy felt mysterious to me. I approached his table with a feeling of déjà vu that brought to mind a pair of bushy eyebrows, cinematic black hair, and thick R’s rolling over an Eastern European tongue.

“Hello, Jack,” I said as I pulled out a filigreed chair and sat down close to him.

“Hello,” said Jack, from a recently shaven but already vigorous field of black stubble, which I thought would probably need some hot foam and a razor before lunch.

We talked casually for a while and I learned that he once worked as a nude model for artists; maybe that’s what made him different. He mentioned a book with an unusual title, and although he strayed several times, he kept bringing it up. “Androgyny,” he repeated, “by June Singer.”

“Why do you keep telling me that title, Jack?”

“I don’t know. Seems to be important.”

He stood up and announced that he would look in the bookstore. He walked into the coffee shop and through a side door into Left Bank Books; a few minutes later he returned saying they just took the last copy from the shelf but he knew I could find it at the library. The title, by suggesting a fusion of masculine and feminine energies had already shaped my interest. Because I had a feeling I would learn something by following my intuition, I promised Jack that I would go to the library in University City and get the book—after finishing my express.

I removed a few coffee grounds from the tip of my tongue and got ready to leave the tiny cup on the little table in the West End when I saw a woman with light brown skin approaching; she wore an orange cloth coat and had inquiring eyes. I watched a falling red leaf touch her shoulder as she stepped up and said, “May I give you this?”

I answered, “Of course.”

She laid her pamphlet upside down on the table; I glanced at a pastoral scene on the back cover, which looked like a dream printed on some kind of persistent denial: workers in fields harvesting bundles of faith and smiles aplenty in an absolutely Christian world. It was the kind of thing I usually resisted when confronted by religious types promoting God that way. I figured I would leave it on the table after she left. I didn’t know that picture would change my life.

The woman with light honey skin buttoned the top of her coat and said, “Thank you.” She moved away and, despite my usual ways, I leaned over and viewed the scene on the back cover of the brochure: religious stuff, the kind I’d seen many times before, and yet, I felt a strange attraction to the image. A limb of yellow leaves in the foreground arched a green valley running all the way to a distant range of mountains. One of the mountains, a little left of center, stood taller than the others.

I didn’t know why but the center of that picture held my attention as if by gravity. Had I followed my first instinct, I would have left the pamphlet where it was and walked away. But after sifting the dregs of my express I stood up and said goodbye to Jack knowing I would take the pamphlet with me.

I got to my car and sat down tossing the leaflet onto the passenger seat; I headed straight for the library in University City with the book on my mind. I tried to ignore the picture, but I caught myself looking at it more than once with a strange sense of wonder. Why would I find such a dopey picture so intriguing? It should have been of no interest to me, but it was like an anchor on my consciousness. It seemed to contain an important message that I couldn’t figure out.

Inside the library I found the aisle for Androgyny; I walked down the corridor of books, and the words Tree and Leaf seemed to leap from the shelf to the corner of my eye. I stopped and read the author’s name; I took the book off the shelf and started leafing through it with a mild sense of shock, realizing that J.R.R. Tolkien, one of the greatest fantasy authors ever, soon would be shedding light on his craft with me. His thoughts were in my hand, and soon I would be home, where he would explain to me how he understood the purpose and meaning of his work.

With the subject of Tolkien’s insight smoldering in my mind, I found Androgyny farther down the aisle. I checked out both books thinking only of Tolkien’s treatise on the serious role of faerie stories. As soon as I got home I began reading Tree and Leaf before I wrestled my jacket all the way off. I draped the garment on a chair and threw the other book and the pamphlet onto the kitchen table. Still reading, I wandered into the living room and took a seat, fixed on the words before me.

I caught a breath of delight and a thrill rose into my throat as I realized that a truly great writer was sharing the secrets of his stock and trade with me—in this little book

I read Tree and Leaf for a half hour before I accepted that my awareness was being tugged randomly from something in the kitchen. I remembered the pamphlet on the table. Without thinking about it, I got up and went to my desk, where I picked up the scissors and walked into the kitchen.

Without a logical reason for doing so, I cut out the center portion of the back page of the religious pamphlet, which I normally would have thrown away, and I carried the clipping into my reading room.

Eager to get back to Tree and Leaf, I slipped the cutting into the pages of the book, so I could see the spray of bright yellow leaves and the valley and the mountains in the distance—just above the book. I wanted that picture where I could see it as I read with no distractions coming from the kitchen. Without asking myself why I was doing this, or why I was attracted to the sunny leaves and all the rest, I returned to Tolkien’s book. I was delighted to receive Tolkien’s ideas on the importance of Fantasy, the most important being his claim that Fantasy is needed by adults.

With the image of valley and mountains and a spray of yellow leaves only a glance up, I read that Fantasy is not like ordinary literature, because “Fantasy does more.” What did Tolkien mean? How did Fantasy do more than other forms of literature? He went on to say: Adults need F

antasy more than children.

That idea was not obvious to me. I thought Faerie stories were for kids.

The great author implied that adults know more about human suffering and disloyalty on an enormous scale, and so they need the benefits of Fantasy more than children do. Since they are more likely to be laden with gloom, adults not only need, but long for, the great gifts of Fantasy—Escape, Consolation, Recovery and Enchantment.

I looked at my new bookmark, a scene in nature that pleased me for some reason I didn’t understand, and I wondered whether adults need to know more than children that good guys win. I closed my eyes and smiled. I silently thanked the world for the printed page, in particular this book by Tolkien. So many years after his death the author’s words could reach out and touch me now. I felt a surge of gratitude in my chest: Tree and Leaf made me wonder whether Fantasy had a healing role to play in the lives of grown up people.

An important purpose in the world.

Satisfying a deep need for consolation—relief in times of affliction—was no small achievement, and the great author said Fantasy does it better than any other form of literature. Despite all odds Faerie stories grant happy endings.

That was true.

Tolkien explained that real Fantasy stories always contain a moment of sudden goodness, which he called eucatastrophe. In a well-crafted Fantasy there is a turning that does more than remove a veil from the story: a real turning takes away a veil that has obscured the reader’s awareness of existence itself by providing a sudden, inexplicable glimpse of primal reality.

I had to stop and think about that.

At the turning of a Fantasy, Tolkien said, a breathtaking glimpse of truth appears, not only in the story but in a revelation of the actual world. It can catapult an adult reader into a state of “joy as poignant as grief.”

I felt my heart pounding my ears: Joy … as poignant … as grief!

Tolkien explained that authors of the “Elvish craft” practice sub-creation: genuine artists of Fantasy plunge into the psyche to embrace primal creative energy—an idea that brought to mind a shaman waking from a mystical trance after consorting with ancestors. Tolkien implied that those who practice the Elvish craft reach for energies that created the world, and thus empower their stories with the force of Creation. All artists, he said, aspire to sub-create, but nature seems to drive some writers of Fantasy to a deeper level—where they touch a mystical power that can trick time and alter reality.

“The magic of faerie stories is not to be laughed at,” Tolkien said.

I wasn’t laughing.

Tree and Leaf consists of an essay on faerie stories followed by a short story by Tolkien. I followed the author’s musings on the great gifts of Fantasy—Escape, Consolation, Recovery and Enchantment—and then, I entered his faerie story: Leaf by Niggle.

It seemed vaguely familiar.

Niggle was a struggling artist who knew he would be obliged someday to take a mysterious, mandatory journey; although he had always been aware of that requirement in the back of his mind, he chose to focus on small things, like painting leaves in the present moment, which he did very well. He preferred to ignore big things like trees or his uncertain future.

Then one day, as Niggle struggled to place a final touch on a pretty leaf, his vision suddenly expanded and his brush went hopping around the canvas like new love. He painted a splendid tree. A few exotic birds came to life under his paintbrush, and a new world came into view.

Niggle built a shed in his garden to protect a huge canvas. This special work of art became the focal point of his life.

Every day he climbed a ladder to serve his calling. Despite his limited talent and the mountains of frustrations worked into his life by his selfish neighbor Parish, Niggle painted with the intention of Picasso, the passion of Van Gogh. Sometimes, in the heart of his heart, he knew he was no match for Rembrandt or Michelangelo, but on his most successful days, after achieving a particularly fine effect, he recognized authentic art in his painting—equal to the very best; in fact, on the very best of those days, he took his work to be the only real painting in the world.

Niggle’s time was running short.

His mandatory journey was coming on. So he struggled mightily to complete the purpose of his life. And his tedious neighbor Parish, a lame philistine whose true gift was being a bore, brought bouquets of difficulty into his life without ever looking once at his paintings. Parish didn’t notice Niggle’s work, but he asked for favors like a plague of locusts. One time Niggle got sick after riding his bicycle through a rainstorm on behalf of Parish’s ailing wife. At first he resisted because he felt his time was running out, and he also guessed that Mrs. Parish was probably not that sick. But Parish was lame, his voice plaintive, so, Niggle could not say no. He peddled his bicycle into the village through a stormy trial of winter rain. And when he got home, he fell under a cloud of ill health. Still, he didn’t let it stop him. He ignored his stuffy nose and his grumpy thoughts, and resisted feelings of woe, because he knew that before long he would be obliged to take his journey: he dedicated himself to his masterpiece.

Niggle gave his best to his art, muttering to himself only occasionally, when Parish came to ignore his work and ask for a favor.

I saw myself in Niggle. I had fallen prey to a deep desire to create something beautiful with words, and, like Niggle, I knew it was beyond my natural talent. I was pressed for time, like him. I hated doing the ordinary maintenance chores of life, like having to work for money, or going out to buy food or clothes, or doing taxes, or taking care of routine needs. Those duties seemed like obstacles to my important work. I understood Niggle, and yet, I could identify with Parish too, because I had stumbled into a broken femur when I was in Paris, and had a gimpy leg, like him.

Finally, the time came for Niggle’s mysterious journey. He boarded a train to a place he had never been. When he stepped off the railroad car, he gasped as he released the handrail behind him. To his great surprise he was standing before the most astoundingly beautiful Tree he had ever seen, beyond anything he ever imagined on his best days. Astounded by the truth of it, Niggle realized that this magnificent tree was his Tree.

Now he could see it all, what the work was hoping for under his brushes. That beautiful spray of golden leaves hanging delicately like a frame over the sprawling valley and the mountains far away. Now standing before his calling, Niggle was stunned. This was the meaning of his struggle. For the first time in his life, Niggle saw the essence of his style, but he wasn’t happy about it because he noticed that the Niggle style was not his alone; as he gazed at the glory of the Tree he realized that Parish, despite their differences and all the bothers that Parish had brought to him, had been essential to Niggle’s artistic process. He didn’t like that; he resisted it; but he had to admit that he owed a great debt to his weird relationship with his neighbor.

Parish had helped him stay true to himself and to his work. It was so ironic. Parish had made Niggle a stronger artist, reinforced his resolve and helped him fashion his style. Niggle had not known it then, but now, he was convinced: Parish had been his partner. It was not an easy thing to take.

In fact, Niggle hated the idea. He despised all the dimwitted indifferent demands forced upon him by Parish. And still, he saw that Parish had improved his work by forcing him to clarify his intent and refine his craft. Niggle blinked hard at the difficult truth embedded in his superb Tree. He followed the beams of his style glowing in all directions from his masterpiece and, despite his desire not to believe it, he saw the work before him as a clear result of a collaboration—with Parish!

Niggle lived in this new land for a while, and then, Parish showed up. The two of them easily set to work, falling right away into a natural rhythm requiring very few words. They seemed to understand each other. They went to work finishing up small jobs and improving things one after the other; they made agreements effortlessly. They made such an impression on the conductor running the train from t

he old world that every day on arrival he cried, “Nig-gle’s Par-ish!”

Near the end of the story, Niggle tells Parish to keep his promise to his wife, and wait for her, while Niggle himself would set out to explore the other side of the mountains. At the end of the tale, back in Niggle’s home town, a guy named Atkins tells his friends that he discovered Niggle’s painting when he repaired Parish’s roof; Parish had used the canvas to plug a leak.

The painting had been ruined by torrential rains during the Great Flood; only one corner was left undamaged. Atkins slowly unfolded the corner of the painting and found a pristine gold leaf. He cut the leaf from the canvass and took it home, but he said it was the whole image, the entire work of injured art that he couldn’t get out of his mind. Atkins bought a frame for the leaf and he took it to the museum but, he said, the complete work would not let him be. “I couldn’t get it out of my mind,” he said.

Until that moment I had identified with Niggle, the little painter, the artist, and maybe a bit with Parish, but now, Atkins just seized my imagination. “I couldn’t shake off the image,” he repeated, “those musty mountains in the distance, and that green valley under a beautiful arch of golden leaves.”

I sat up straight.

I looked at my picture.

The one I couldn’t get out of my mind.

Above the pages of the book was a branch of golden leaves over a green valley and a faraway range of mountains, which I had cut from a religious pamphlet. “You can find Niggle’s painting of the leaf at the museum,” Atkins said. “It’s in a dark corner on a wall: Leaf by Niggle.”

I looked up again at the bough of golden leaves and something inside me moved; all of my old assumptions shifted away at once; the old rules seemed no longer to apply. With a sudden jolt of recognition I found myself in a new state of being. I knew the world, through a new faculty of awareness. I was now cognizant of everything—inside and out—all at once. I saw a few mystical characters on the edge of my vision. I thought they were ancestors and ancient men of kindred spirit dissolving into a foggy past.

The Book: A Novel Calling

The Book: A Novel Calling